I recently watched Jed Mercurio’s TV drama Bodyguard – I had been excited to see it, having gotten utterly wrapped up in his masterly Line of Duty and having heard how he had the British public on the edge of their seats for six weeks waiting to see what would happen next. But that didn’t prepare me for how brilliant it would be. Yes, I was edge-of-my-seat sucked into it, but upon finishing it, I also realized with exhilaration how Mercurio had done that to me as a viewer – through the carefully constructed, clearly thought-through structure of the story.

(WARNING: Plot spoilers below! Stop right now and treat yourself to the show if you haven’t seen it yet … then come back and read this …)

Now don’t get me wrong – there are many elements in Mercurio’s writing that make Bodyguard great TV.

He places impactful contrast on the surface of the story that creates a range of dynamic charges and sizzling conflicts; such as how his two leads are Julia, an upper-class English woman, older, cerebral and plotting, right-wing, a politician who is making and perhaps breaking the law versus David, a working-class Scotsman, younger, intense and physical, hates and resents her politics and their results, a policeman who is charged with defending the law. Or the contrast in his forces, how Mercurio makes almost all the top end of the Home Office and Security Service white, upper-class and middle-aged, the establishment, the old order, while his cops investigating are working-class mixed-race (Indian, black, east Asian). He also presents an ongoing thematic contrast between the driving forces of different sides, between expediency versus principles: for example, between the antagonists of organized crime (killing is “just business”) and the terrorists (“money is to buy more guns”). One of the things that makes Julia such a great character is that she has the internal conflict between both: her ambition to lead that will drive her to blackmail – but also the sense that she genuinely wants the RIPA bill to pass because she feels it will protect people. (And indeed in one way, she is proven right, in that her adversaries kill her to stop it, because it would have impeded their capacity to commit crime).

There are so many excellent elements in Mercurio’s writing. How he keeps the audience on their toes, with red herrings and misdirection – everyone is deceiving, who can we trust, the long-present question of could even David be deceiving us, with his smarts, lies and war-trauma motivation, could he be behind the assassination all along? The boldness of the drama’s scale, risking melodrama, of a realistic story whose reach involves cops, politicians, spies, ex-army, organized crime and terrorists. His great dialogue (“It goes without saying I know where you live”). How he treats PTSD respectfully. How he manages for the tale to be both utterly addictive and riveting, and yet also often powerfully moving. I could go on and on.

But for me, more than anything, what makes the story so engaging, so involving, and so ultimately satisfying, is its structure — and how so many of its key elements are set up in triangular symmetry.

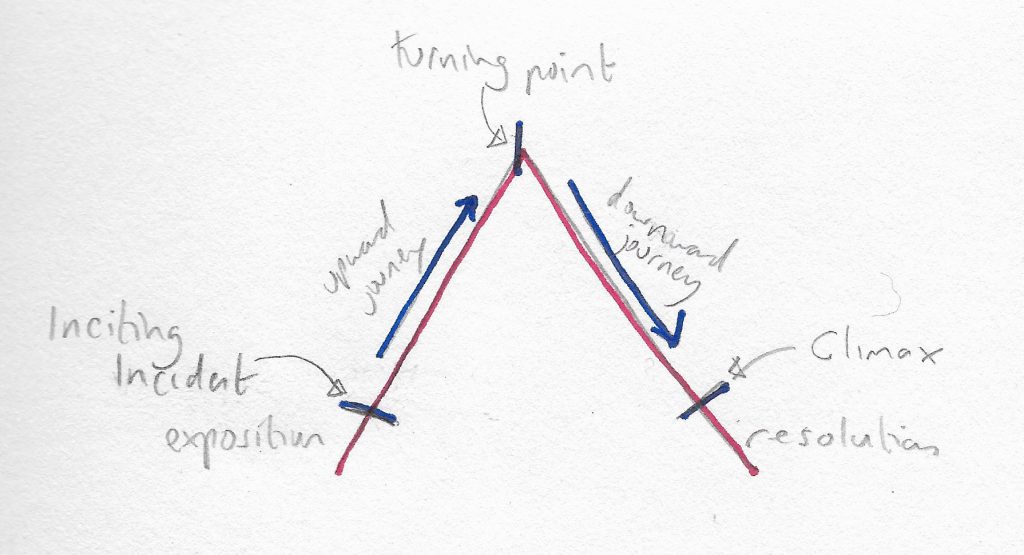

Mercurio sets it up like any classic story — enough exposition to set the scene, then an inciting incident that takes the protagonist off on a new, adventurous direction, a turning-point mid-way through the story that changes everything and sends us off into a totally different direction, that ultimately leads to the climax (which we only now see was unavoidable from the inciting incident) and depending on how that goes, the resolution.

Diagram A: Basic Generic Story Shape

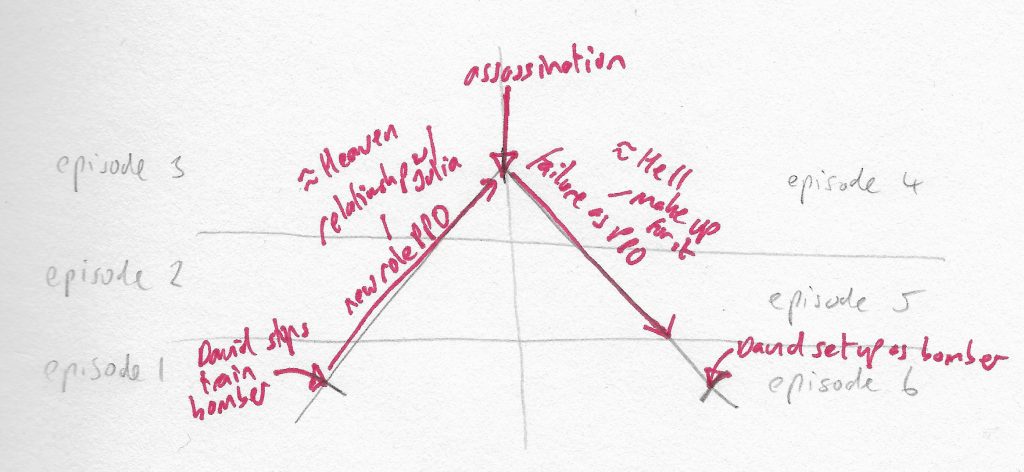

The basic shape of Bodyguard is: an inciting incident of David heroically preventing the bomber on the train, which leads to his being promoted to being the Home Secretary’s PPO (Personal Protection Officer, her bodyguard). David then gets drawn upward into a relationship with Julia, until her assassination. At this very centre of the story, the height of the triangle, we have the turning point of Julia’s murder – where David realizes he has failed as her bodyguard … and also that maybe Julia’s not the biggest problem, he’s been too focused on her as the danger, and all along it’s been someone else worse. Then we have David’s downward spiral until the climax of the suicide vest, and the restorative resolution of his catching out those behind the assassination and attempted coup.

On the upward track, surrounded by luxury, fancy hotels, limos, big houses, filled with purpose, in a thrilling secret sexual relationship with a beautiful woman who values and respects him, David is in a form of Heaven. But in giving into these choices, of pleasure and ego over principles, David gets more drawn into sin. On the downward track after he loses Julia, David spirals into suicidal despair, in a world of rainy streets at night, dingy internet cafes, embarrassing scars, removal of his power and mission and dignity and support, alone – he’s in his form of Hell, but where ultimately he doesn’t give up, but tries to make up for the sin and failure as a bodyguard.

Diagram B: Basic Shape of “Bodyguard”

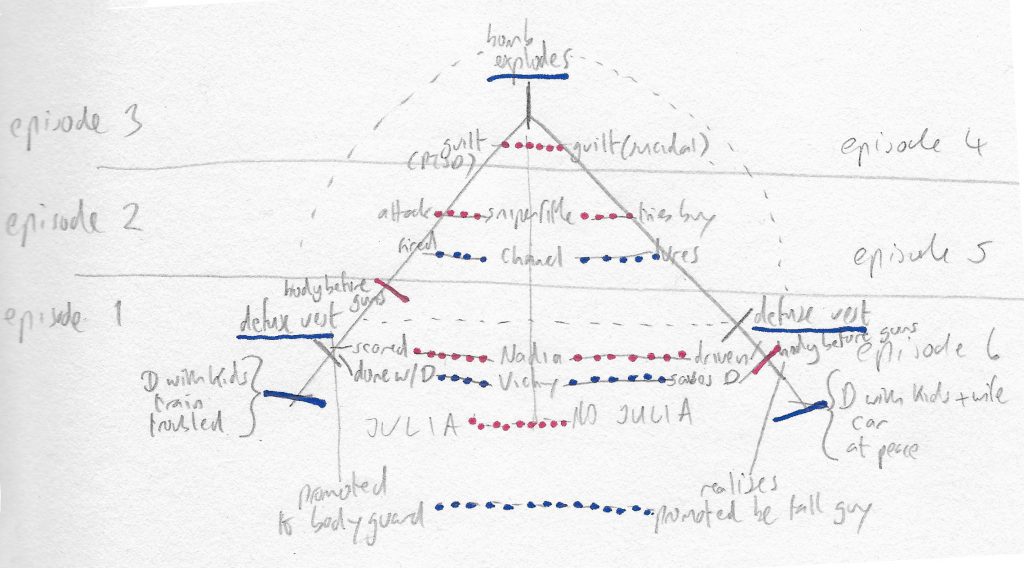

But what’s incredible, brilliant, hugely effective, is just how many elements of the story match up from one side of the triangle directly across to the other side. Here’s just a few examples:

- The inciting incident and the climax both involve successfully defusing a suicide vest. (While the mid-point assassination involves a bomb – but one that goes off).

- How Mercurio gives us Julia for the first 3 episodes, making her an equal character to David in our interest, a couple we care about, then kills her off precisely at the end of the first half — and leaves us without her for exactly the second half. (Even though there’s a part of us that keeps thinking, c’mon, she can’t really be dead?)

- The inciting incident involves the terrified muslim terrorist Nadia – so the resolution involves us finding out Nadia is no scared victim, but a driven jihadi engineer who made the bombs.

- At the start of episode 1, David is on a train, with his kids coming south from visiting his parents, lost in problematic thought. At the end of episode 6, David is in a car with his kids and his wife, going north to visit his parents, finding a new sense of peace with his PTSD and his life.

- In Episode 1, we discover how Vicky, David’s wife, has given up on him to the point where she is now sleeping with someone else, she is done with him, his PTSD-affected violent behaviour is too much for her to handle. So we have the magnificent, powerfully moving moment in Episode 6, where she risks her life to save him.

- Additionally, in Episode 1, David puts his body in the way of guns to protect Nadia. In Episode 6, Vicky puts her body in the way of guns to protect David.

- The contrast between Episode 1, where David does not trust the police not to shoot, and Episode 6, where the police don’t trust David not to set off the bomb.

- The contrast of a bomb in the most confined possible space (a train toilet) versus a bomb in the open space of a park.

- The use of guns: the two key points when guns are fired — on the upward track, the sniper attack which leads to Andy shooting himself (successful) versus on the downward track, David’s attempt at shooting himself (unsuccessful). And indeed how in Episode 5, David tries to acquire the exact same sniper rifle that was used by Andy … in Episode 2.

- David’s guilt at attacking Julia in Episode 3 … and his increased suicidal guilt at failing to save her in Episode 4.

- In Episode 1, how ex-soldier Andy is disgusted at David’s profession in becoming a cop; in Episode 6, how ex-soldier David states his pride at serving alongside cops of honour like Deepak.

- How we have Chanel the PR advisor getting sacked and David ushering her out in Episode 2, and we don’t see her again til … exactly Episode 5, where she draws David into the trap with organized crime.

- And of course, in Episode 1, David’s promotion to Julia’s bodyguard … versus his discovery in Episode 6 that his promotion was not only not down to merit, but only so he could be the fall guy for her murder — could there be anything more opposite to a bodyguard?

Diagram C: Triangular Symmetry in Story Structure of “Bodyguard”

Okay, that’s all very clever, screenplay nerd (and likely astrologist and conspiracy nut), but that doesn’t mean anything for me, the normal viewer.

But I’m sorry, it does. This is not just Mercurio leaving clever clues and easter eggs behind for his super-fans to find — these structural elements are the foundation, the beams of the house, the frame of the car, that make the story work, that draw us in and feel satisfying as we’re drawn along them, even if we can’t see the skeleton behind the flesh.

Because in this lean, hard-won and deliberate way, Mercurio gives us information, gives us set-up on one side … and then pay-off on the other. We never get coincidences from nowhere, no deus ex machina saving the day, what occurs is satisfying and makes sense. Even though we don’t see it coming — we’re too busy being in the present moment of the riveting story — it makes complete sense when we get to each revelation or big moment. It surprises us, but also feels right. Because of the natural, considered shape of the story, the recurring yet contrasting images, ideas and events resonate with us, pleasingly. And we also don’t end up with bits of narrative, repetitive scenes, wandering sub-plots, that don’t add to the story. All that’s there is meant to be there — and that’s why there’s no let-up in our attention. In other words, brilliant storytelling.

Now I don’t know if Mercurio consciously works like this — probably it happens more in the rewriting, the editing and cutting and fixing, but it’s definitely creatively deliberate, it’s no accident. The lean building of a story with such tightly knitted set-up and pay-off, in terms of plot and emotional journeys, treats your audience with respect, and takes them on a satisfying journey. Many meandering, repetitive writers of the so-called Golden Age of TV could learn a lot from Bodyguard … they’ll definitely have a good time watching it.

***