I recently watched a terrific documentary about the groundbreaking theatre producer and acting teacher Wynn Handman (it’s called It Takes A Lunatic, and it’s currently on Netflix, well worth a watch). He really was an extraordinary figure – he set up the groundbreaking American Place Theatre in New York which provided a crucial bridge for more experimental playwrights like Sam Shepard to reach the mainstream, and taught acting classes right up until his 90s, with his students having included Richard Gere, Denzel Washington, Connie Britton, John Leguizamo and Alec Baldwin, to only name a few who became famous afterwards. I realized he had still been teaching while I was living in New York, and I had a pang of regret that I’d never studied with him. I’m sure I’ve had learnt a lot. He was my kind of teacher – gentle, probing, funny, with high standards, but never destructive, always encouraging; recognising the fragility of any actor in a class who is taking a chance on stretching themselves and vulnerably trying something new.

But it also made me think of how lucky I have been with the great acting teachers I did study with – and how much I’m hopefully bringing from them as I start to teach more myself.

I ended up being very lucky in acting study, in that I went to a British-style full-time two-year drama school – but I also took many classes in my ten years in New York, where it’s considered very normal for an actor to keep learning and studying throughout their career, particularly in the early years while you work. So in many ways I had the best of both worlds.

But I never did acting classes as a kid – I’m sure I would have loved them but it never really came up, I didn’t really know it was an option then (it thought it was all musicals and tap-dancing and sparkles).

It wasn’t until I was working a full-time graduate job after college that I first took an acting class. I had had a life-changing experience acting in a production of Juno and the Paycock my last year of school, but after some initial success in the Dramsoc at UCD, my acting interests got lost in the fog and fireworks of student politics and personality clashes.

While working this rather well-paying but ill-suited corporate job, I felt this urge to try acting again, to not give up on it. (I found myself reading Shakespeare speeches into the mirror of the men’s bathroom on my tea-breaks so I guess the desire was pretty strong!) So (and this rather reveals my age!) I looked in the Yellow Pages for acting classes, and found the Gaiety School of Acting and auditioned for their part-time Foundation Course in Acting. I got super-lucky. Because I would see later on how people can lose years from acting by being shrunk or scared by a bad teacher. But my first acting teacher was a gem.

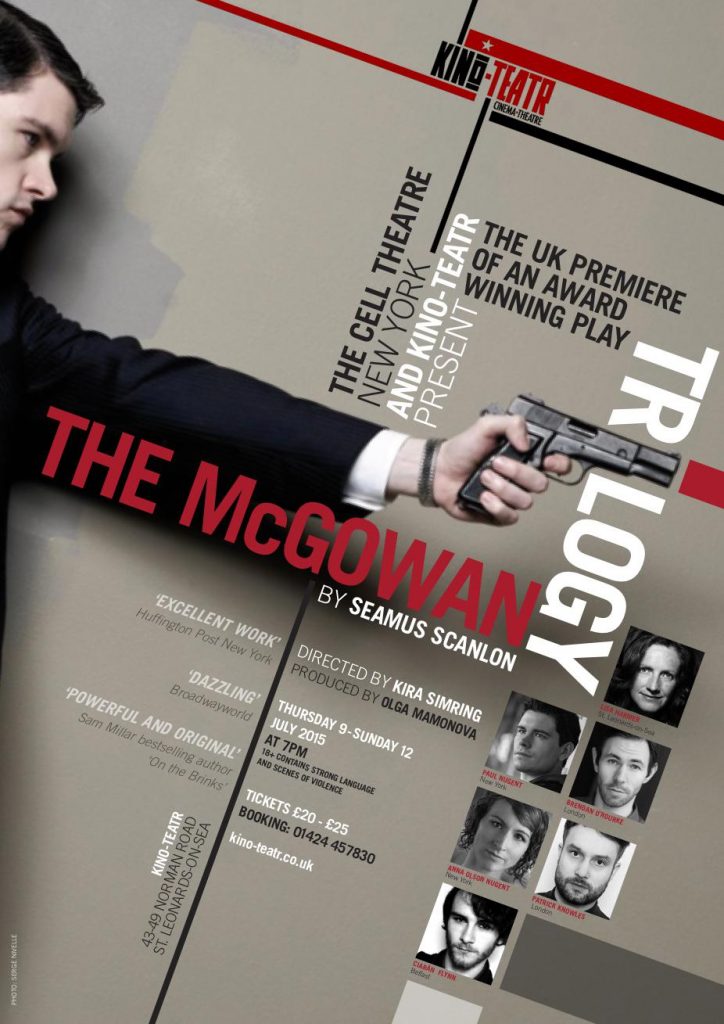

Robbie Taylor was from the North of Ireland and had done drama school in London. After adventures there, he was now in Dublin writing for a soap opera. Robbie in many ways should have been a stereotypical acting teacher – black leather jacket, cheeky with a swagger, full of anecdotes and loving his pint. But there was a spark in his eye and a real vigorous love of the work – and of actors. On my first evening in class, he asked what was the basis of all drama, and I blurted out “conflict.” There was a moment of silence where he stared at me in surprise; then he broke into a smile as he noted that was the right answer; we clicked right away. He saw something in me, and quickly pushed me to more and more challenging material, from a monologue from Long Day’s Journey into Night, through a comedic scene in a Cockney accent, right up to a very dark scene from David Mamet’s Edmond for my final showcase scene. For someone with very little experience but a massive hunger to learn, he fed me, pushed me, roared me on, and always urged me to “go for it.”

I came out of his class knowing the job had to go and I needed to go to full-time drama school. That summer in a dusty room above the Norseman pub, Robbie helped me prepare my two monologues for my audition, and when I was accepted into the Gaiety School’s full-time course, he celebrated with me what felt like a shared triumph.

Drama school for me was bliss. Spending two years, 24/7, just working on acting, surrounded by acting, endlessly talking about acting, was amazing. I went from having one acting teacher – to over a dozen. Of course, a lot of the time it was extremely hard. I was in bottom of the class for dance, had a singing teacher tell me to be “a little less Boyzone,” and found mime a mystery. I felt very behind the others in my class, most of whom had a lot more experience than me. At times, I felt physically awkward, shy and lacking in any star quality. But not once did I consider quitting. Even at its most painful and humbling, even humiliating, I loved it. I had great teachers, who were generous and gentle, probing but patient. And like a flower being tenderly cared for, I grew. By the end of two years, I was still in the bottom of the class for dance, but I was a hell of a lot better than when I started, and was rocking African boot dances; we changed singing teacher and I found my voice, ending up singing a lead duet in our showcase at the Gate Theatre; and with my classmate Ewan we put on a mime scene that made people cry. The lessons I learnt from my voice teacher Cathal Quinn I still apply to this day, right down to my pre-show warm-up. And I had acting teachers like Maureen White, Mark Lambert and Eric Weitz with real-world experience of New York and London that drew me up and showed me all different kinds of plays, and approaches to the craft, and I graduated with a completely empowered set of skills and a buoyant desire to create on the stage.

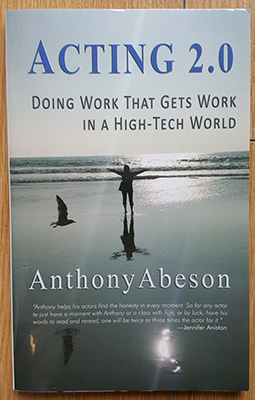

When I moved to New York a few years later to learn more about acting in one of the great theatre cities, I was hugely keen to find a weekly scene study class like the ones my heroes had taken early in their careers (I’d long been hugely inspired by the photo of Paul Newman in class that I’ve pasted above). It took me a while to find the right one, but eventually I ended up with Anthony Abeson. A casting director sent me to him, saying he was the teacher that she recommended actors study with to really get their acting chops before appearing in TV shows and movies. When I learnt that he had convinced Jennifer Aniston that she should explore her potential as a comedic actress after seeing her in a scene from Chekhov, I certainly was intrigued. When I joined his class, it was a revelation. With his glasses, beard, tweed jacket, fast-moving pen and gigantic smile, he had the air of a mad professor – and his notes and adjustments and exercises were often pure genius. Having trained himself with Stella Adler and Lee Strasberg, studying with him I was only two degrees removed from Stanislavski himself. But while that appealed to my ego, Anthony was all humility. He challenged us, but he never made it about him. He always looked to drive us to be braver, deeper and realize just how much creative capacity we had, and what a noble role the actor has, even if it’s often in an industry that feels shallow and cruel.

In a classroom that was a wonderful cross-section of ethnicities, Anthony encouraged us to examine and make a weapon of how we would be stereotyped, but also to explore and expand our possibilities, as we “have the universe inside us.” He insisted we do our homework deeply, that we “flesh out” every element of the script with imaginative detail (so that if I talk about a memory in a scene, I have pictured in my mind what that was, not just having a vague idea or a predecided emotion). He insisted that we had great responsibility as actors – that when we played a character, we represented everyone who had been in that situation, so we should take it seriously (for example, if we were playing someone who was sexually assaulted in the past, we represented everyone who had been). I studied with him twice a week for two years, and I definitely grew hugely from it (even if some of his improv exercises and the play we put on were seriously whacky!)

But he wasn’t the only great teacher I had in New York. I studied with Rich Topol, who was then and is still a working actor (with nine Broadway credits at last count, and film work including working with Daniel Day-Lewis on Lincoln). From Rich, I learned so much that was practical – from a more senior actor but still a peer. About breaking down a scene, about when I was faking versus when I was playing, about the meaning of silence and pauses, about making monologues dynamic. And he didn’t just teach in class – he pulled back the curtain on the craft. One day, he snuck our select group into the tech rehearsal for The Merchant of Venice on Broadway that he was appearing in. Sitting in the dark watching Al Pacino and the cast working and reworking scenes, and with Rich bringing cast-members up to talk to us on their breaks, I learnt a huge amount just in one afternoon.

And I also studied with Bob Krakower, a revered film acting teacher. As he had been the casting director on possibly my favourite TV show NYPD Blue, I had to resist just spending the whole time asking him about working with Denis Franz, but from him, I learnt so much about the essentials of knowing the given circumstances of the scene – and then putting myself in them. About how an actor’s homework can be complex – but really performance is simple (but that doesn’t mean it’s easy!)

And that is only to name a few of the great teachers I worked with there.

In recent years I’ve been doing more teaching myself, and it’s been wonderful to see the benefits of a good acting class from the other side.

Initially I started to see it as I worked as a trainer and coach for companies and universities, using the tools of theatre to help them rehearse real-life situations and empower their work skills. Working on corporate roleplay with doctors and dentists, with lawyers and managers, it’s been amazing to see people grow in empathy as they’ve seen, for example, a feedback session, from the other person’s shoes. In coaching entrepreneurs on their pitches, it’s been remarkable to see people who, when I first met them claimed they were terrified of public speaking, stand up in front of a packed hall of VIPs and deliver creative and passionate presentations.

But really most strikingly I’ve noticed it since I’ve started teaching an acting class myself. Recently we’ve opened our theatre company’s Great Plays Gang to the public. It’s sort of like an acting class crossed with a book club, where we explore a new great play each month, including reading the whole play aloud as a group and then delving deeper into working on specific scenes. It’s very much inspired by my acting class experiences in New York, in that it is an ongoing class, that we have a range of experience in the room (from people who are taking their first steps into acting up to actors with 20 years experience keeping themselves in shape) and that we make it a safe, relaxed, positive space in which hopefully creativity can bloom.

It’s been very powerful and moving to see people grow in the class. To watch them bravely take chances. To observe them stepping towards their acting dreams and see them succeed – often surprising themselves. To watch them delight their classmates. To see them respond to and gain from the suggestions I’ve been able to give them. To be present as they expand in self-belief as artists. And it’s been deeply meaningful to hear our Gang Members tell me how they’ve rediscovered their love of acting; often after a harrowing or hurtful prior experience that made them step away. And to be told how they’ve gone back to their “real lives”, to their day-jobs and relationships and daily routines, with increased confidence and refreshed creativity, how their friends and family can see how happier they are – even just in the way they’re walking around the house! To see all this value they are getting from it – not just in the fun and camaraderie and play of the class, but in how it impacts them in the rest of their lives, has made me see just how valuable a good acting class can be. As we like to say with our theatre company, “theatre makes life better.”

I know it has for me. So when I heard that Wynn Handman passed away this year, it made me stop and think. I saluted him as a great acting teacher, and hoped I could maybe be a fraction as good as him, have as much impact on my students, encouraging them to grow in themselves and in their love of theatre and performance and joyous creativity.

And so I say to you: if you need a creative outlet, maybe think about an acting class. You might be a little nervous about it, but if you find a really good one, you’ll be adding something special to your life. And hey, you never know what it might lead to …

You can find more on AboutFACE’s Great Plays Gang acting class at aboutfaceireland.com/great-plays-gang/

***

He’s a bit like the red squirrel, that lovely Irish creature, rather gentle and delightful, who is being routed and pushed aside by his rapacious and rude American cousin, the grey squirrel. The red is now disappearing from Irish woodlands because some fool introduced the grey to his environment, and the grey is much pushier, more aggressive and rather less soulful, and so is taking over and pushing aside gentlemanly ol’ Red.

He’s a bit like the red squirrel, that lovely Irish creature, rather gentle and delightful, who is being routed and pushed aside by his rapacious and rude American cousin, the grey squirrel. The red is now disappearing from Irish woodlands because some fool introduced the grey to his environment, and the grey is much pushier, more aggressive and rather less soulful, and so is taking over and pushing aside gentlemanly ol’ Red.

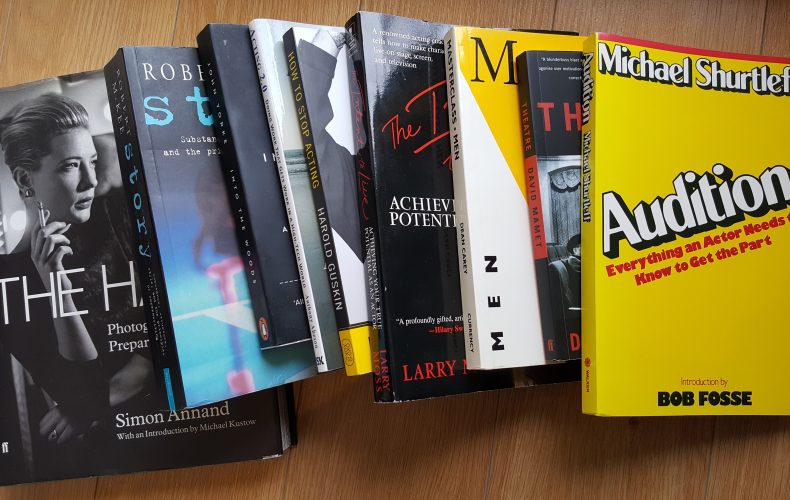

I don’t know if there’s a book that produces more creative juice for an actor when preparing for an audition (or frankly any performance of a script) than

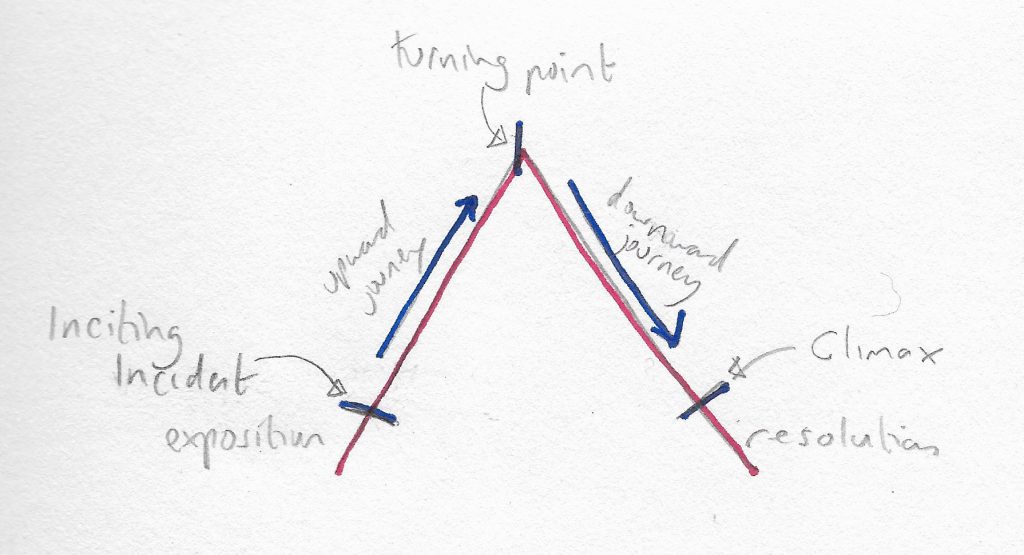

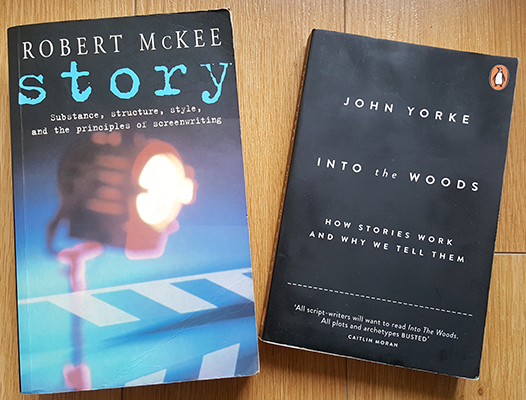

I don’t know if there’s a book that produces more creative juice for an actor when preparing for an audition (or frankly any performance of a script) than  I am a deep believer that actors are storytellers – not puppets on a string, but artists who bring their insight and creativity to bringing a script to life. They owe a honourable duty of care to deliver the writer’s story to the audience as best as they can. To do so, they must understand not just their role in the piece, but the story as a whole. How it is structured, how it builds. As such, I think there are two texts that are truly genius at helping us to look at scripts and divulge their blueprint, find their foundation, see the gorgeous lines of their construction, and those are Story by American screenwriting teacher

I am a deep believer that actors are storytellers – not puppets on a string, but artists who bring their insight and creativity to bringing a script to life. They owe a honourable duty of care to deliver the writer’s story to the audience as best as they can. To do so, they must understand not just their role in the piece, but the story as a whole. How it is structured, how it builds. As such, I think there are two texts that are truly genius at helping us to look at scripts and divulge their blueprint, find their foundation, see the gorgeous lines of their construction, and those are Story by American screenwriting teacher  This is a book I have only come across recently, and found it really invigorating.

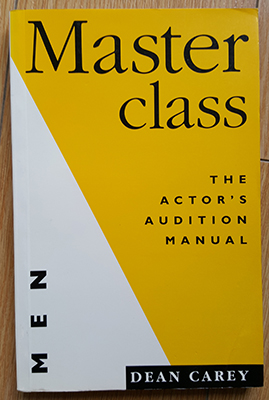

This is a book I have only come across recently, and found it really invigorating.  I love this book. I initially picked it up in late ’90s before going to drama school, because it had over 100 monologues in it, so I could find a great one to audition with. Indeed it does. But the gold in this book is the range of hugely practical exercises that its author, the Australian acting teacher

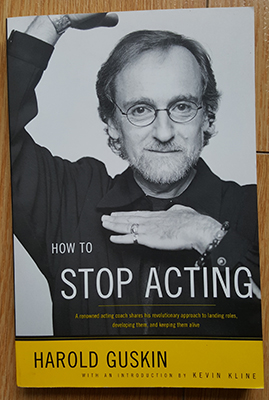

I love this book. I initially picked it up in late ’90s before going to drama school, because it had over 100 monologues in it, so I could find a great one to audition with. Indeed it does. But the gold in this book is the range of hugely practical exercises that its author, the Australian acting teacher  Now I am going to state up front my conflict of interest here: this is the book by my old acting teacher in New York,

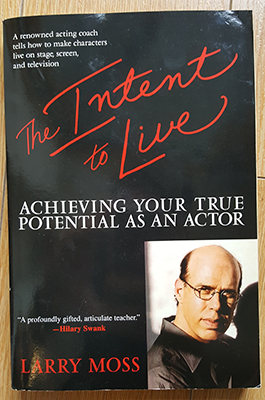

Now I am going to state up front my conflict of interest here: this is the book by my old acting teacher in New York,  When you are ready to be challenged by a hard-ass teacher, there’s one man to go to –

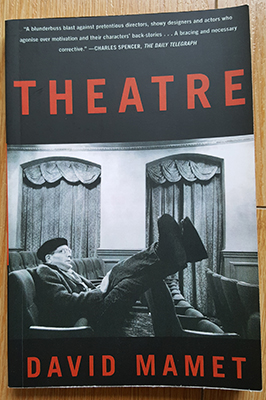

When you are ready to be challenged by a hard-ass teacher, there’s one man to go to –  Now obviously Mamet is a master playwright and a very powerful thinker about the craft, and you wouldn’t go wrong reading any of his books.

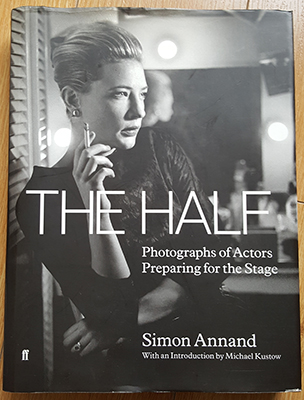

Now obviously Mamet is a master playwright and a very powerful thinker about the craft, and you wouldn’t go wrong reading any of his books.  Maybe now you’re done reading – but there’s still one more book to see … and it is gorgeous and spine-tingingly inspiring to look at. It’s

Maybe now you’re done reading – but there’s still one more book to see … and it is gorgeous and spine-tingingly inspiring to look at. It’s